|

Depth of Field: Is more always better? Note: This photo tip

page requires a firm grasp of the concepts

of depth of field and how it is

correlated to focal length and

aperture. I'm assuming the reader

has a basic knowledge of these concepts.

Any good photography book (not just

underwater ones) will cover this in enough

detail to bring readers up to speed for

this photo tip. (Yes, this article was written before the digital age, but the concepts are still 100% accurate.) Obviously, I hang around a lot of

underwater photographers. I lead photo

trips, teach photo classes, give out

advice (sometimes unwanted!) and hear a

lot of underwater photographers talk

photography. I'm often surprised how most

people discuss depth of field. It is

obvious to me that many of them understand

the concept but not the application of

depth of field in underwater

photography. When we're talking about having money,

more is always better, but when we're

talking about depth of field, more is not

always better. Often it is better, yes.

Always? Hell no. Many photographers never

shoot a macro lens any wider than f/16.

They buy the largest flash units in the

world so they can blind everything

shooting at f/22, or in the case of an

extreme macro lens, effectively at f/44 or

f/64. Why? "Because more depth of field is

better" they say. Why? I'm here to tell you that more is not

always better. Before I argue the point,

let me start with a story. Once upon a

time there was a fantastic underwater

camera called a Nikonos. Unfortunately, it

was not an SLR, so the photographer could

not actually see through the same lens

that the film would be exposed through.

It's what we call a rangefinder camera,

meaning that the photographer looks

through a window on the top of the camera

that approximates the view of the camera.

Because the viewfinder is always in focus

(your eye does the focusing), you can't

tell by looking through the viewfinder if

the lens is focused correctly on the

subject, so you have to guess. If you

guess that something is 4 feet away and

it's actually 5 feet away, the picture

might be out of focus. If you guess 4 feet

and it's actually 4.5 feet, it might be

close enough that the focus will be okay.

With the Nikonos, everyone wants as much

depth of field as possible to compensate

for the inaccuracy in focusing. When

shooting with my Nikonos and 15 mm lens in

open water and ambient light (as I do with

large marine mammals) I like to have

enough depth of field that I won't have to

refocus too often. Sometimes animals are

moving too fast and all I can hope to do

is shoot away and concentrate on

composition. If I know that I have good

depth of field from 3 feet to infinity, I

really don't need to worry at all about

focus unless the animal comes really

close. This is handy. Unfortunately, the Nikonos has taught

generations of underwater photographers

that more depth of field is better. This

has carried over into macro photography

where most people are dealing with

extension tubes or SLR's with autofocus.

In this case, we no longer need depth of

field to compensate for the inaccuracy of

focusing. The Nikonos framer tells us how

far away to put the camera for proper

focus, and the SLR can focus accurately on

the subject. For extreme macro work, (let's pull a

number out of the water here...say 1:3 or

closer) the reproduction ratio of the lens

limits the depth of field significantly,

and most people want to shoot at f/16 or

f/22 to be sure that the subject is in

focus from the front to the back. It can

be kind of annoying to have a fish eye in

focus but the lips (closer to the camera)

out of focus. This is a good time for

maximum depth of field. However, at reproduction ratios

somewhat less than 1:3, shooting with

maximum depth of field can be a detriment

to the image. Why? Having a lot of depth

of field can make the background very

sharp and distract the viewer from the

subject. Furthermore, lenses are sharpest

in the middle of their aperture range

(around f/8). Due to diffraction, at f/22

most lenses are somewhat softer than at

f/8, even though they give more depth of

field. This huge interest in maximum depth of

field is very common in underwater

photographers. It is much less common in

surface photographers. Portrait

photographers rarely shoot at f/22. They

know that a person should stand out from a

background. If you shoot at f/4 to f/8

(depending on the reproduction ratio), you

can get enough depth of field to keep the

entire face in focus but throw the

background out of focus. This is important

because the eye goes to the sharpest thing

in a photograph. If the idea is to draw

one's attention to the face, you don't

want the trees in the background to be

sharp. They distract the viewer and

clutter the photograph. Same thing

underwater. You want the fish in focus and

the background a little soft so the fish

stands out and the background doesn't

interfere. A common trick in television is to run

closing titles of a film over video that

is ever so slightly out of focus, shot

that way on purpose. This makes the titles

very sharp in comparision to the video,

and makes them jump out better and be

easier to read as they scroll by. It's the

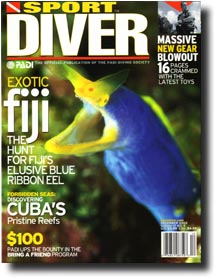

same concept. Now here's a real life example. Figure

1 is the cover of Sport Diver

featuring a photograph of mine taken in

Fiji. It's a blue ribbon eel sticking out

of the reef. Many people commented on how

this eel seemed to jump off the page. I

got several questions when this cover came

out from people who wanted to know how I

made it look so three dimensional. I sold

several prints of this image. What was the

trick? No trick. I shot the image at f/8, f/11

and f/16, knowing that if I shot too

stopped-down, the reef in the background

would be in focus and distracting. I

didn't know exactly which f-stop would be

best, so I experimented. When I got the

film back, the f/16 image was too sharp in

the background. I sent the f/8 and f/11

shots to the magazine and the editor chose

the f/8 version (a horizontal) and blew it

up and cropped to a vertical for the

cover. With the face of the eel

razor-sharp, the image was able to be

enlarged and cropped to a vertical no

problem, and with the background nicely

out of focus, the text on the magazine

cover seemed to jump right off the page.

Most photographers when faced with a

situation like this simply set it on f/22

and blast away, because "more depth of

field is better". I can tell you for

certain that the f/16 versions of this

image were not nearly as stunning. They

were not cover material. Without the f/8

version of this shot, I never would have

gotten the cover of this issue.

Furthermore, at f/8 I was only shooting at

1/4 power on the strobes, so they recycled

instantly. Gotta love that! People often think of composition in

terms of 2 dimensions. Think of depth of

field as your 3rd dimension in composition

and think about how much you need to make

the impact you want. I'm not saying that

f/22 is bad. Often f/22 is the best answer

to the depth of field question...but not

always. How about another example? The other

effect you get by opening the aperture (in

addition to a reduction in depth of field)

is an increase in the amount of ambient

light that reaches the film. Most

underwater macro shots have a black,

underexposed background, even when shot in

broad daylight, because at f/22, there is

simply not enough ambient light to

register on the film. By opening up to

f/11 or f/8 and shooting upward slightly,

you can get some nice blue water in the

background of a shot rather than a boring

black background. Well, that's tip #1. I hope you enjoyed

it! Jonathan Figure 1: Blue Ribbon

Eel at f/8. Note that the background is

out of focus, thus making the face of the

eel and the text on the page jump out in a

3D-like effect. Learn underwater

photography on Dive

Adventures

with Jonathan!

|

Last Update 12/20/02